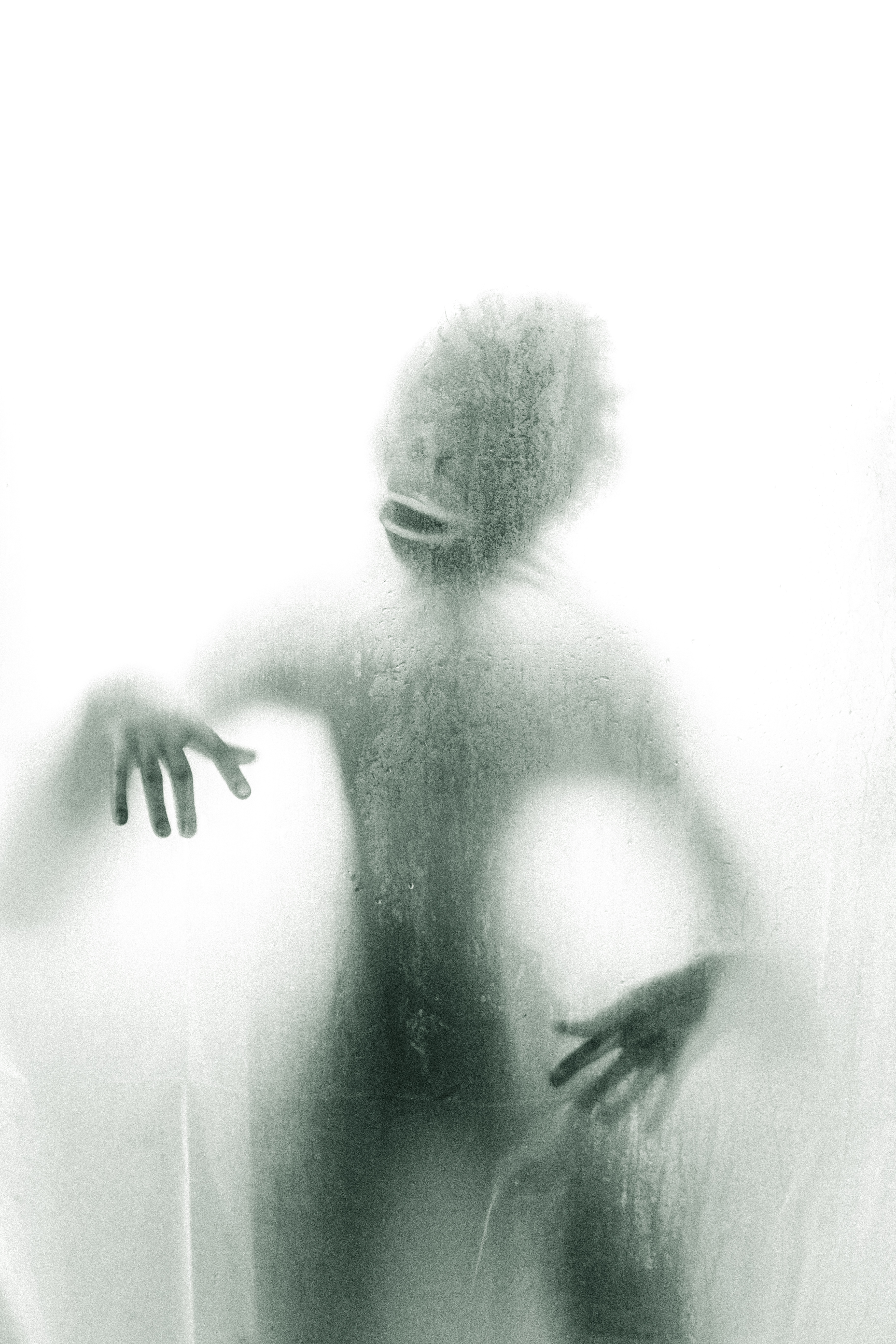

Have you ever watched a thriller about demon possession? Kind of off my usual beaten path, I know, but you’ll see where I’m going with this. I promise. Anyway, I like them sometimes. Every so often, I’ll check around for a good one to watch and see what piques my interest. I’ve found that sometimes I’m drawn to thrillers that make demonic possession of someone their central plot. (Which is surprising to me because I’m not usually interested in seeking out super dark stories about evil, especially when there’s more than enough of it to be found in the news). About once every three or four years, one of these dark plotlines pulls me in and I find myself watching an unsuspecting upstander begin the struggle of (and for) their life.

When I find a good possession thriller, I like almost everything about it. I like the journey the character takes from being ok (or pretty ok) to decompensating to being pretty possessed most of the time to being fully possessed all the time to finding progressive healing to being stronger and more conscious than when their story started. I like the tension over “will this character we’ve all come to love make it through this?” I like the research and deep inquiry that the other characters employ in an effort to find out more about the demon that is in possession of the victim.

What I am particularly drawn to, what I appreciate most is that there’s always ample time given to the journey taken by the characters in finding out the particular nature of the demon and its name. When the demon is called by name, its possession breaks. The demon always gives clues as to who they are, but they’re usually abstract and steeped in about a million layers of epic composition of poetry and require a doctorate in theology. At some point, to the rest of us, it pretty much seems like a lost cause. Just in the nick of time, someone puts all of the pieces together and discovers the name of the demon. Then we feel that surge of renewed hope.

What I’ve noticed is that, in all of the stories that I find most gripping, there are at least five commonalities:

- There is a specific name of the demon, which when finally discovered and uttered face-to-face to the demon is the only defense against it.

- The possessed or loved ones of the possessed enlist help.

- The demon seems to have limitless ways of manifesting itself.

- Someone, whether the possessed or loved ones of the possessed, experiences self-doubt, retreats, somehow finds the motivation to throw themselves into the metaphorical fire of terror and uncertainty, and contacts the demon for a head-on battle.

- The demon never really goes away. It’s still there lurking around, but now the characters have more strength, courage, willingness, and awareness to deal with it.

I appreciate the symbolism because darned if that just isn’t that just how life is.

Whether it’s depression or anxiety or addiction or a particular pattern of behavior or thought pattern or chronic pain or the fear of fear or general dispiritedness, we all go through periods of life when we feel utterly possessed by pain and completely out of control. And many of us have found release through inquiry about the name of our experience or feeling and asking for help from loved ones, peer groups, and professionals.

Many of us have realized that our demons never completely go away, but that our relationship with them changes, and that with each bout with and experience of those demons, we learn to sit with whatever they bring. Through this long, uncomfortable process, we’re learning that our demons have many, many ways of manifesting themselves in our lives. We’re learning to coexist in a world where demons can’t be extinguished but instead faced with self-compassion, willingness, and courage. We’re learning to stop believing the bullshit they spew in an attempt to maintain their control over us. We’re becoming more connected with ourselves and with others, with life.

Keep on keepin’ on.

Love and Be Loved,

Natalie