I’m a huge fan of the TV show, The Office. There’s an episode during which boss, Michael Scott, says something to his employees about wanting to make an announcement. He starts talking and an employee, Oscar Nunez, says, “These aren’t announcements…” Michael says, “Yes, they are; you just don’t care about the information.” And we do this kind of thing all the time with each other.

Productive communication is just as much about the way we hear something as it is about the way we say something. I see a lot of couples who try therapy specifically because they want to address the way they communicate with one another. This usually doesn’t mean what they think it means.

There are a million ways we send each other messages- by doing something (or not doing something), the way we ask, when we ask, arguing, avoiding arguments, passive-aggressively, literally a million (or more) ways.

Most of us think that when our partners accept an idea, think we’re right, or validate our self-concept we’re experiencing “good communication.” If we disagree, argue, or are invalidating of each other’s self-concept we believe we’re experiencing “bad communication.”

A breakdown or disturbance in our communication can happen when we don’t like the messages we’re receiving. We stop talking or argue in circles. Sometimes we acquiesce to one another’s demands or plans. We’re still communicating, but it’s become unproductive because we don’t like the information; the messages don’t make us feel good. We try various efforts to get the other person to understand what we are saying. We think, “Well if they really understood what I am saying, they wouldn’t react this way.” Sometimes that’s true. Sometimes, though, we just disagree with each other or can’t manage our emotions around conflict, and no amount of rephrasing will change that.

What do we do when someone knows exactly what we want, they just don’t want to (or can’t) give it to us? What if one person wants a lot of deep, personal conversation and the other person doesn’t? Or what if what one person thinks is a lot of conversation, the other person thinks of as minimal? Going from here, it wouldn’t be that hard for one partner to feel like the other is emotionally withholding nor for the other partner to feel constantly under attack.

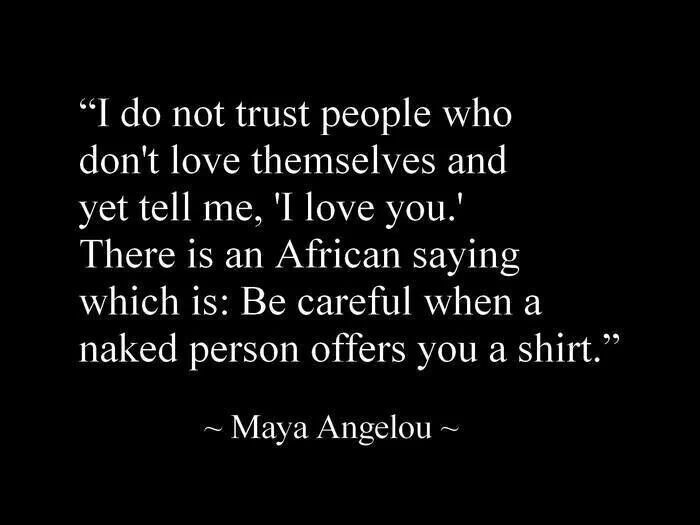

Our need for a reflected sense of self is often the culprit. Don’t get me wrong, in the moment it feels great to have someone validate us, our ideas, experiences, and feelings. But we can’t plateau here. The drive for other-validated communication can end up being a relationship killer.

Here is an example of other-driven need for validation:

“I want to tell you about myself, and then I want you to understand, validate, and accept me. I’ll tell you about myself and then, to make it equal and to make me feel safe, you have to tell me about yourself regardless of your desire to share. Whatever I disclose, you must make me feel that you are trustworthy and you must disclose something that’s just as revealing, if not more. This is how we will deepen our intimacy and develop trust.” This is most common. In a dynamic like this, the person who requires less intimacy is the one in control.

Here is an example of self-driven validation:

“I want you to know me, to see me, to hear me. I believe that in order for you to really love me, you first have to know me. I know that I am taking a risk by sharing this with you, but it’s a risk I’m willing to take because 1) I want to see the real me and 2) I know that I am capable of taking care of myself in the face of rejection. My sense of safety in this relationship is not dependent on your validation of me. You don’t have to disclose something to me just because I have disclosed something to you. I acknowledge and accept that we are separate, different people.” This is a lot less common. In this dynamic, control isn’t relevant. It’s about the intimacy and security made possible by self-support.

The road from other-validation to self-validation is not short, and it’s not at all easy. Most of us grew up in families where other-validation is the ideal. It’s also pervasive in our greater culture. Self-validated intimacy takes acceptance, self-confrontation, practice, and commitment. We have to be willing to know and accept ourselves first. We have to have a willingness to be curious about ourselves and to face things we don’t like.

So what are the benefits of shifting from the aim to be validated by others and the aim to validate ourselves?

- Vulnerability doesn’t have to be a four-letter word anymore.

- We stop being dependent on an other to make us feel loved and important.

- We learn that we can disagree without turning it into a knock-down-drag-out fight.

- We stop taking disagreements personally.

- We trust ourselves.

- We break free from feeling controlled by someone else.

- We stop having the kind of conflict that ruins our whole day or week.

- We get to know the other for who they are, not for the role we need them to play.

Changing communication patterns isn’t always about empathy, active listening, acceptance, and reciprocity. Those are great skills to have, but they won’t necessarily bring your relationship back from the brink. If you can bring yourself back from the brink, your relationship has a better chance.

“Communication is no assurance of intimacy if you can’t stand the message.”

-David Schnarch, Ph.D.

Love and Be Loved,

Natalie